Affordable Housing – Part1 The Problem We Have Today

Affordable Housing

Part 1: The Problem We Have Today

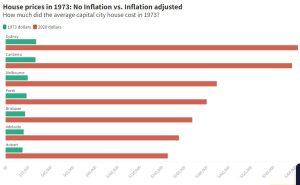

Over many years, different Australian governments have attempted to do many things to deliver affordable housing but the outcome has been totally appalling with house prices continuing to rise at a far greater rate than disposable household income. Now most households are two income families, not like the single income families as it was in the 1970’s. The following link can show the relationship between housing and income in those past 50 years.

https://www.savings.com.au/home-loans/australian-house-prices-over-the-last-50-years-a-retrospective

This graph clearly shows that the current approach to inflation and house prices is not delivering anything near affordable housing, but is, in fact, delivering the absolute opposite! One needs to question the whole approach of the management of our economy by Federal government and Treasury at least as far back as the 1960’s.

Essentially the way the economy is currently managed is through the RBA (Reserve Bank of Australia) controlling the interest rate and the money supply. The banking sector looks to the so-called “cash rate” announced by the RBA to set their interest rates. So what is the “cash rate”?

The “cash rate” is the interest rate on unsecured overnight loans between banks – essentially, the almost risk-free overnight interest rate on unsecured loans between banks. Loans between banks is to cover cash shortfall that may occur if depositors withdrew funds thus depleting the level of cash on hand for the next day’s trading requirements. Banks will adjust the interest rates that they charge for a variety of loans they provide for their customers, and, as well, how much interest they will offer their depositors (mostly these rates change a lot slower than the interest charged to borrowers).

The other banking adjustment affecting the economy is the level of the deposit required on the types of loans. The terms of a housing loan in the 1970’s meant a deposit of between 20 – 25% of the value of the house being bought, as well as a savings history of at least 5 years that would show the capacity to pay. This was also underpinned by an employment history that would show a sustainable income for the duration of the loan. However, in 2022, the deposit required is sometimes as low as 5% of the sale price, with the income test being far less stringent. This brings more people to the market place to purchase each and every home, thus causing an upward pressure on house prices.

The other lever is the money supply which is managed by the amount of currency in circulation. Before the digital currency age, to increase money supply more currency (bank notes) was printed, and to decrease money supply with currency (bank notes) being deposited into banks, it was withdrawn from circulation, thus reducing the money in the community.

As well the banks can ‘expand’ the money supply many times over, lending to other customers – on paper, at least, by using the deposits of their customers to make loans to other customers. The bank can lend out a % of the depositor’s funds if the “loan” is a secured loan, then further loans on that total can be lent out, thus ‘increasing’ the money supply. For example, if a bank receives a deposit of $1,000, it must retain 10% of that at the bank, so that $900 can be lent out to another customer. If this is a ‘secured loan’, then it is considered that the “banked” assets of that bank have expanded to almost $1,900, and it can therefore further lend out 90% of that “banked asset” amount, which would be about $1,810. Meaning that the bank has effectively lent out $2,710 from the original $1,000 deposit – this can be further repeated to the extent that the RBA permits, thus increasing the money supply. This is why we hear about the private and public debt in connection with the economy, and at times wonder ‘why so much debt?’. The brake on this expansion is yet another lever the RBA has as it sets the limits of that ratio as the RBA determines to what extent to expand the money supply. This is a deposit multiplier.

The reserve requirement ratio determines the amount banks must keep in reserve, and the amount banks can lend, creating additional deposits. The ‘deposit multiplier’ depends on the reserve requirement ratio. Fractional reserve banking enables banks to increase the money supply through lending excess reserves.

In this age of digital currency, that is overlaying our economy, the Government’s debt can be expanded to make payments to overcome catastrophic economic events by just adding a few zeros to a loan from the RBA to the digital money supply. While this can be very inflationary, the Government can equally withdraw a few zeros to make a re-payment of the loan from the RBA. This is called the New Monetary Policy where it is possible to move to zero interest rates on deposited accounts. This direction in economic terms is unpredictable in knowing where in practice this will go, but it could cause the full control of an economy via the government through the RBA and the levers that are pulled from time to time. There are some strong directions from the World Bank to move away from physical currency and become more dependent on digital currencies.

We need to remember that money is what money does! This concept can be difficult for some to understand, but that is the way it is.

The current measuring of the health of the economy is by looking at the growth of the GDP (Gross Domestic Product), but this is not a good measure as far as I am concerned. The GDP is calculated by the “number of times that a dollar circulates around the economy”. The problem of this measure is that in inflationary times many more dollars are circulating to purchase the same, or even fewer, products. A more accurate measure is to determine the % of disposal income, especially of low income earners after the essential items of basic housing utilities and food are deducted; if this % is increasing, then the economy is improving; if it remains the same we are flat-lining, while if it is declining (as it has been for some time), it means the economy is in trouble.

Apart from the financial side of housing affordability is the supply of housing, which is affected by the rate of population growth (both natural increases and immigration) and the growth of new housing. To retain stable housing prices, the supply of housing must be at least equal to the increasing growth rate of the population. Another factor in the mix is the fact that the sale of the housing stock in Australia is open to almost any person in the world who desires to purchase housing in Australia and has the means to so do. This situation is vastly different to most other countries throughout the world, where the purchase of housing is limited in some countries to only those with citizenship rights, or those who have permanent residency standing in the country and have thus qualified by the number of years of living in that country. Other countries permit a % ownership by non-nationals that is always less than 50% of the value of the real-estate.

There is much we could do here to place a large downward pressure on the cost of housing. We must not forget either, that connections to work locations from residential areas will influence the price of housing as well. There is a lot to consider when one looks at the problems and the potential solutions to the housng problems.

This pretty much sums, in basic terms, up the problems of affordable housing as it currently stands in Australia.

To be continued ………..

oooOOOooo